excerpted from Views from the Sleeping Bear  Until she died in 1995, Laura Basch lived on a homestead deeded to

her grandfather-in-law in 1874. The deed to the property, once framed

in her living room, bears the signature of President Ulysses S.

Grant. The original log cabin built by Nicholas Basch in the 19th

century still stands within the walls of the home Laura Basch left

behind. Her home is privately owned now by a group of local families

who plan to preserve and maintain it. They still keep an elaborate

flower garden at the site, as Laura Basch did throughout her life. Until she died in 1995, Laura Basch lived on a homestead deeded to

her grandfather-in-law in 1874. The deed to the property, once framed

in her living room, bears the signature of President Ulysses S.

Grant. The original log cabin built by Nicholas Basch in the 19th

century still stands within the walls of the home Laura Basch left

behind. Her home is privately owned now by a group of local families

who plan to preserve and maintain it. They still keep an elaborate

flower garden at the site, as Laura Basch did throughout her life.

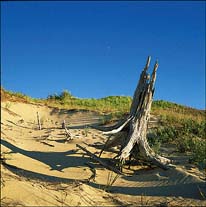

The Laura Basch farmstead is just one example of the human history chronicled by the Port Oneida Rural Historic District. The district, on the National Register of Historic Places, has been recognized for the significance of its architectural and agricultural features, as well as for the stories these homesteads tell about early European settlers to the region. At the end of Miller Road, the barn built by Frederick Werner in 1855 is all that remains of John Miller's 19th century farm. A small foot trail north of the barn leads through the trees to the Werner family cemetery, hidden along a ridge. Another hidden marker of the past is the tiny sugar shack at the end of a row of sugar maples southeast of the Dechow/Klett farm. Although it is barely visible from M-22, the shack is a great discovery site for those willing to hike up the ridge formed by the moraine behind the farmstead. Two other structures also add to the understanding of the historic district, but they tell of the much more recent past. The Burfiend farm dates back to the first settlers of Port Oneida: Carsten and Elizabeth Burfiend. They built their first home on the beach at Port Oneida where it was exposed to both weather and thieves. One account recalls Mrs. Burfiend and her children hiding in the rafters while pirates ransacked their home, taking what they would. In another story, Mrs. Burfiend carried her children up the steep dune while a November storm took their home into the Lake Michigan surf. To avoid the dangerous exposure, the Burfiends rebuilt on the ridge above the beach. That house was incorporated into the one their son, Peter Burfiend, built in 1893. Later, a second family home was built on the same site. Both houses still stand along the ridge, and visitors to the Lakeshore can stand where Elizabeth Burfiend watched the storm take her home. Lilac bushes, the only grave markers for Elizabeth and Carsten Burfiend, grow next to the remaining Burfiend homes. If visitors look  out to South Manitou Island from the back porch of that house, they

will see a picture that has essentially remained unchanged for

centuries. Inside, old beds and faded draperies are still in place,

left by the Burfiend descendants when the home was acquired for the

National Lakeshore in the 1970s. A rose bush, unattended for more

than 20 years, still blooms by the door. out to South Manitou Island from the back porch of that house, they

will see a picture that has essentially remained unchanged for

centuries. Inside, old beds and faded draperies are still in place,

left by the Burfiend descendants when the home was acquired for the

National Lakeshore in the 1970s. A rose bush, unattended for more

than 20 years, still blooms by the door.

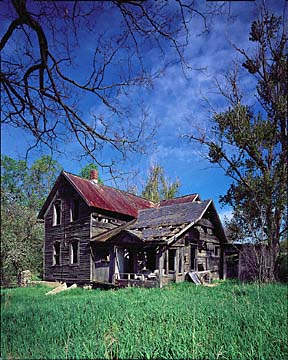

North of the Burfiend home, Baker Road turns right off Port Oneida Road and follows a ridge through the trees to the Martin Basch Farm (pictured above). In Farming at the Water's Edge, the authors describe the farmstead as being "in an advanced state of deterioration (91)." They are being generous. Abandoned before 1970, the house has succumbed to the forces of weather and vandals. It remains an example of how quickly the human history of the region could disappear. visit Thomas Kachadurian online at: www.kachadurian.com.

Copyright 1998 Manitou Publishing Co., Thomas Kachadurian & Sleeping Bear Press • All Rights Reserved. |